Spiraling out of control

Hisham Ashkar

07.10.2021

The exchange rate in itself means nothing. If one USD is equivalent to 1,500LBP or 1 million LBP, this in itself means nothing. But if the exchange rate intrinsically lacks meaning, it impacts anxiety and fear, backed by faits (not only facts but things that are done or made). Fear and anxiety of higher prices, fear and anxiety of not making a living are accompanied by the concretization of what we are afraid of and anxious about. But this can only be realized if we live in a static reality with only one variable: the exchange rate, in practical terms, to correlate and to dictate the cost of living[1] according to what it was in US Dollars.

Some can justify this by the cost of exports, but how can this be justified regarding locally produced commodities? How to explain that a couple of months ago, the price of Taanayel yogurt was slightly higher than that of Zott (produced in Germany), while salaries are still static in LBP (that lost 90% of its value). Fuel prices have not increased (at the time). Machinery and cows already existed in Taanayel farms and so on. How do we explain that the factory price of one brick produced by Müller (a 100% Lebanese brick factory in Mazraat Yachouh) is 0.75 USD?[2] In contrast, the market price of a brick imported from Italy, Spain, or Egypt varies between 0.75 and 0.9 USD? Needless to say that until a few months ago (at the time I checked the price), salaries and cost of productions were still comparatively the same in LBP compared to the pre-2020 period. At the same time, hundreds of thousands of bricks manufactured before the economic crisis were stacked in the factory’s backyard. The list drags longer and longer beyond these two examples.

It will be simplistic to name greed as the answer. It is rather endemic to capital accumulation processes and to the boutiquier mentality of local industrialists. This mentality came back in force all over the world with the return of capitalism to its liberal/neoliberal phase. I’m singling out the industrial bourgeoisie because the steep depreciation of the local currency coupled with salary stagnation should greatly benefit them, from dominating the local market to immensely boosting their exports. Alas! Most of them are nothing but short-sighted boutiquiers.

But still, this is not the point. This is just the consequence of a static world with one variable approach. An idea of a world consolidated by a government and a central bank gluing the official exchange rate to 1507.5 LBP for the dollar, while everyone, even they, do not believe in it. But this is an efficient way for an economic elite, i.e., the bourgeoisie, to hoard most of the money and wealth of the rest of the population.

Let’s go back to the beginning. An exchange rate does not have a meaning in itself. But what mainly matters is the relative stability of the exchange rate and the purchasing power. The exchange rate is basically currency conversion between two currency zones that are somehow sovereign (total sovereignty is a myth). Economic factors can impact this exchange rate, but not in general. Otherwise, how do we explain that some heavily indebted economies, such as the United Kingdom, have not yet seen their currencies plummet? In brief, currencies are mainly based on trust, faith, and, of course, on law enforcement. The exchange rate is also heavily dependent on these factors. A fluctuation in this conversion would mainly impact imports and exports, benefitting one at the expense of the other. In many cases, it would lead to inflation, pushing up prices of commodities. And that’s what we are experiencing in the Republic of Lebanon. And that’s what is the main issue at stake now, with prices increasing tenfold while wages remain stagnant.

In this situation, a simple solution would be to raise salaries. In fact, some countries like Italy would depreciate their currency on purpose, so to boost their exports, with lower prices, Fiat would outsell Volkswagen worldwide, at the same time they would raise salaries, not quite in the same percentage as the currency depreciation but enough to counter substantial part of the increase in prices. Therefore, the question is not related to the exchange rate or the depreciation of a currency but rather to inflation and purchasing power. In addition, most of the time, inflation occurs independently of fluctuation in the exchange rate. So this current price situation in Lebanon has not been seen in the light of currency depreciation but rather from the perspective of inflation. Therefore, contrary to the wisdom of economic orthodoxy, the best way to deal with such an event is to increase purchase power. But, of course, it depends on your point of view. Should society be at the service of the economy, or should the economy be at the service of society? Needless to say that increasing the power of purchase should not be reduced to a simple wage raise. Still, rather it is a transformation in the economic and social approaches. Therefore it is better to identify it as providing or even instituting an economic guarantee for the population, for all the population.[3]

Concerning the former, it seems an obvious statement. Relative stability is a necessity not only for economic activities (mainly imports and exports) but also for every aspect of life unless one is either an adrenaline addict (even, in this case, one would pause and take a rest from time to time) or an adventurist and opportunist… “chaos is a ladder” to quote an eminent intriguer. But this does not apply to the vast majority of society. However, relative stability is by no stretch of the imagination a synonym of staticity. As in Banque du Liban, staticity has kept the exchange rate fixed daily at 1,507.5LBP to USD since December 1997. A feat worthy of a Guinness world record entry, just next to chef Ramzi’s largest hummus plate. But how to blame them? After all, they consider economy and finance purely as mathematical equations, formulas, and models, as natural science (the prevalent economic orthodoxy). Even for most people on the left, this subject became taboo because they considered changing the exchange rate would worsen social conditions. Yes, this can happen (as is the case now), but it is neither a necessary condition nor a predetermination. Most people on the left tend to forget that the exchange rate stabilization has little to do with preserving social conditions. Above all, it is a mercantile issue. To borrow a previous example, to avoid Fiat and Volkswagen and the related car merchants going into a price curtailing competition, that eventually will harm these concerned parties. Nothing is more ruinous to “free trade,” aka the liberal economy than price uncertainty and steep competition. Since the dawn of capitalism, fixing exchange rates was the main preoccupation, tying it to gold, then to the US dollar. It preceded the creation of the European Union with the establishment of the exchange rate mechanism, which gave way later to the Euro. The Euro is mainly a static exchange rate, more than a currency.

Fixing exchange rates can present many dangers, especially if a currency is considered to be fixed at a higher rate than it should be. The best example is Black Wednesday when speculators, led by Soros, broke down the Bank of England. Luckily for the Republic of Lebanon is that nearly no one outside Lebanon cares about Lebanon. Yes, this might be hard to swallow for many Lebanese, and it might hurt their egos. But international speculators did not see it worth it to speculate on or to short the Lebanese currency. Even major investors shied away from investing in Lebanese bonds and their alluring interest rates. Simply, it was not worth it for them. The magical exchange rate in Lebanon worked brilliantly from 1997 till 2019, mainly because the main local speculators were kept under control. In the 1980s and in 1992, the main speculators against the Lebanese pound were the Lebanese banks. The post-war economic and financial arrangement established by Banque du Liban was based on two pillars: a fixed exchange rate (mainly for the benefit of big merchants) and public debt (mainly for the benefit of banks). The latter also acted as a form of stabilizer to the former. Because most government bonds are in LBP, this impedes local banks from speculating on the currency since they will be speculating against themselves.

No matter how deficient a system is, as long as people believe in it, this system keeps on working… till a point, a breaking point. The economic crisis in Lebanon was decades in the making. To put it briefly, it is the result of economic and financial models instituted since the 1990s. In this post, I will not discuss what led to the economic and financial crisis of 2019. Still, I don’t consider that the currency issue and fixing exchange rate (though artificial and in a critical condition) played any significant role. On the contrary, the currency crisis resulted from the economic crisis, in which the banking crisis played a hegemonic role.

Lately, and in a typical anachronistic fashion, blooming narratives are positioning the currency crisis at the start of the past two years’ chain of events. People took to the streets on October 17, 2019, because of the depreciation of the Lebanese pound, they say, and so on. But, of course, the currency crisis and the subsequent price inflation are the dominant issues now; they even eclipsed all other issues and crises. However, this is factually incorrect. Placing events in their historical timeline provides a different narrative. It is quite right that the deviation between the official exchange rate and the black market began on August 1, 2019. It is also quite right that some people were worried about this situation. Even a talk on this subject was organized in a private university. But no! People took to the streets because of an economic situation that continuously degraded for years.

August 1, 2019, was not an exceptional event. In the past few years, and on several occasions, the exchange rate in the black market (i.e., authorized money-changers… if they are authorized and have a license, how can this be labeled as a black market?) differed from the official one. For example, political or economic events affected the black market exchange rate as economic pressure was mounting. This happened in November 2017 after the prime minister of the Lebanese Republic was held hostage in Saudi Arabia. This also happened in January 2019 after Moody’s downgraded Lebanon’s rating. But this divergence usually took place for a short period before aligning again on the official exchange rate.

Interestingly, the change in the exchange rate on August 1, 2019, was not directly related to some major political or economic event. There seems no direct event led to this divergence. Apparently, it was related to the accumulation of economic pressure and the lack of related political actions. But one must not forget the affair of Jammal Trust Bank (JTB). For months, there were talks of having it on the US sanctions list. The decision on sanctions was looming. So the reaction of the exchange market can be in part in anticipation of that decision. By the end of the month, August 29, JTB was officially sanctioned by the US treasury.

This, in turn, was the trigger for the banking crisis. It was not the cause; it was simply the trigger. Some large depositors began to withdraw their deposits. Banks began to implement some restrictions (limiting online LBP to USD conversion from midnight to 6 in the morning). Of course, the banking crisis unfolded spectacularly after October 17, as banks took the opportunity of mass protests to impose strict restrictions. It is relevant to assert that mass protests did not lead to banks imposing restrictions. Banks took the opportunity of mass protests to appropriate depositors’ money. Banks were de facto bankrupt before October 17. Due to all these events, the exchange rate on the black market remained higher than the official one. Still, it did not lead to any spectacular change in exchange rates.

Moreover, this had little impact at the time as the price of most goods and necessities remained stable for months. And it wasn’t till January or even February 2020 that the price of commodities began its ascension. It wasn’t until the first covid-19 curfew in March of that year until the price breach opened wide. At the time, there was still a timid or naïve feeling in the air that a solution for the crisis could be found. But, as months passed, as the limbo prolonged, as the inactions of those with decision-making powers were multiplied, any remaining trace of hope or trust evaporated.

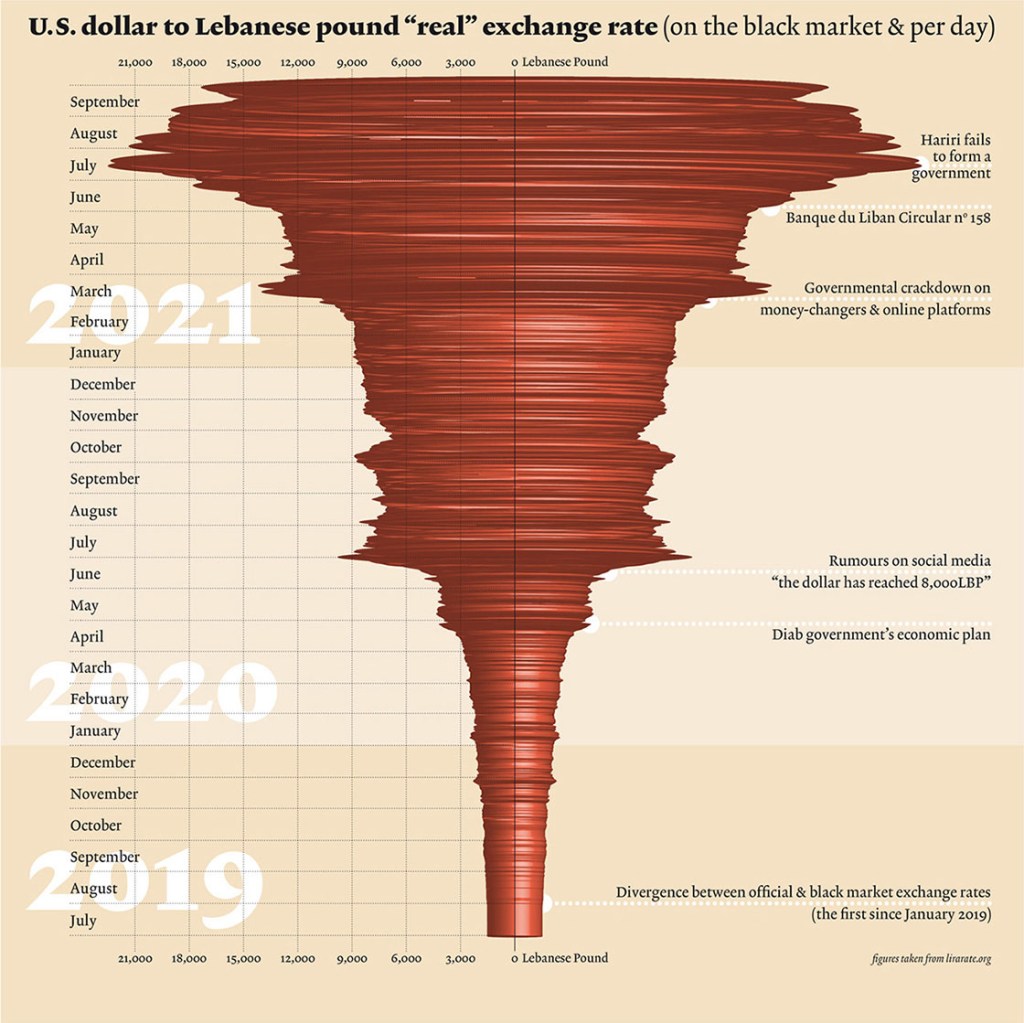

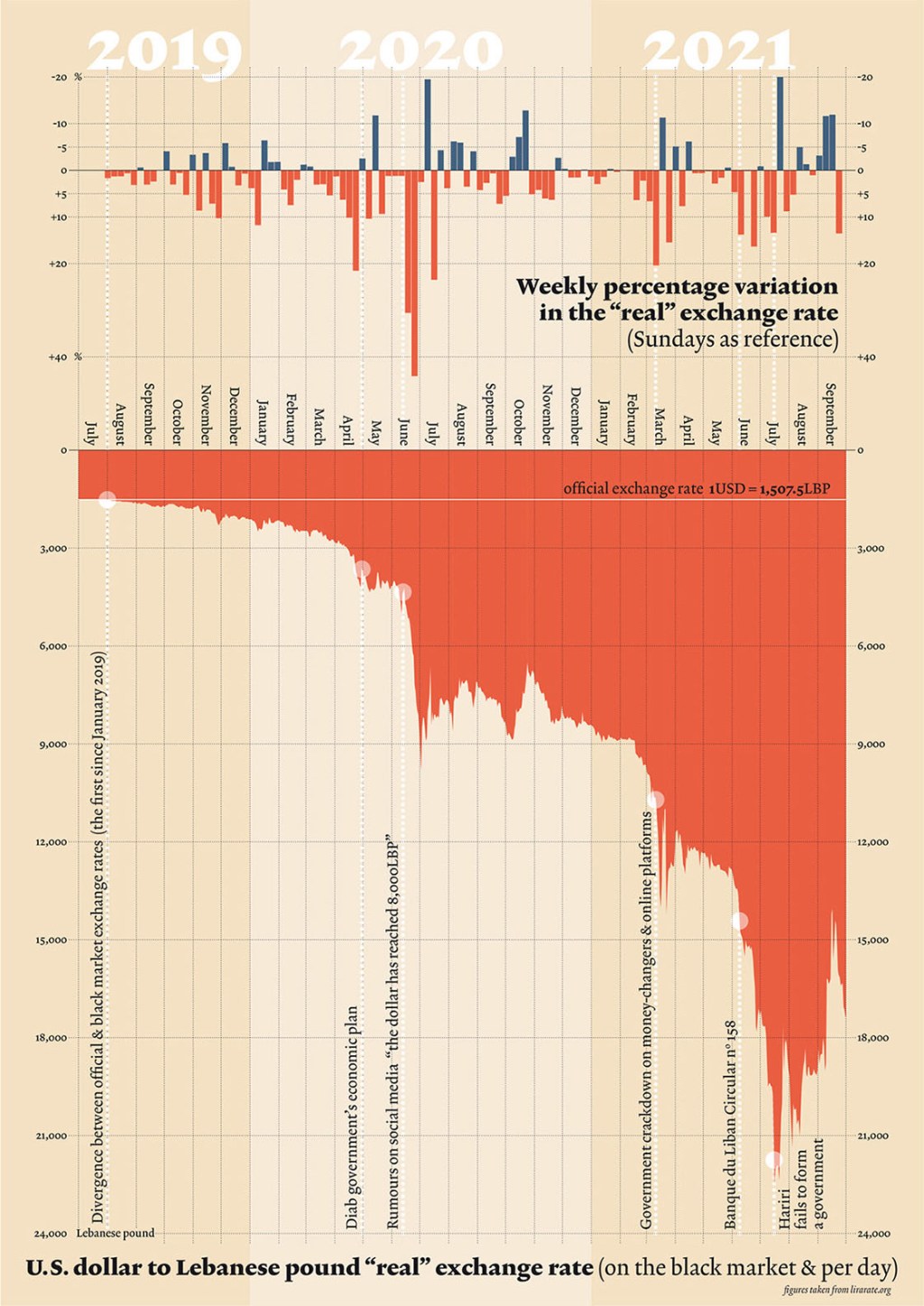

The course of the depreciation of the Lebanese pound can be roughly divided into four parts, let’s call them plateaux. While there are many reasons for the continuous depreciation of the Lebanese currency, and some were discussed earlier, the direct causes for reaching each plateau have little to do with major events in the past two years. And we’ve experienced quite a lot of them. They were cascading in a frenzy one after the other.

The first is the 4,000LBP to the dollar plateau that began in late April 2020. The main reason to reach this phase was the government’s economic plan. In it, on pages 9 and 10, the government unveiled its exchange rate policy, “to move to a more flexible exchange rate.” A poorly drawn graph showed the government’s intention to gradually depreciate the Lebanese pound till it reaches 4,297LBP for the dollar in 2024. Although the plan was not officially announced until April 30, drafts of the plan were already in circulation much earlier. Natürlich, the market reacted, the dollar began its ascension. By the time the plan was announced, the dollar had already surpassed 4,000LBP on the black market. I’m not sure if the government plan reeks of naivety or of ignorance. Still, if one deals with economy and finance as a natural science (as the orthodox economy does) and ignores the social aspect, the social would come back and hit them hard. If a government announces the planned depreciation of its currency, except that it will depreciate immediately. It is a question of faith and trust and the lack of them. In a way, it is reminiscent of what the British government did during Black Wednesday. As the pressure on the pound sterling mounted and the Bank of England was depleting its reserves, the government twice in one day announced raises in interest rates. From the orthodox economic perspective, this is the right thing to do because raising interest rates will bring investors, increasing the power of the pound. However, speculators read it differently (apparently, they were asleep during economic and finance classes at university). They interpreted it as a panic move by the British government. They doubled their efforts until the pound went into a freefall.

The second is the 7,000-8,000LBP plateau. As the state of inaction and uncertainty lingered, a rumor circulated on social media that the dollar reached 7,000LBP. This was around June 10-11. The exchange market experienced a lot of disturbances, and the dollar began a fulgurate ascent to reach the promised number in less than two weeks. At the time, nearly everyone was expecting (and fearful of) a further depreciation of the pound; some were even anxious that the dollar would reach 20,000. A common effect of anticipation was at work. It was enough for some people to announce it in public for it to become a reality. The third plateau, 12,000LBP, was also reached in another typical manner. Try to impose something by force, and it will backfire. In early March 2021, the government launched a crackdown on money-changers to control the exchange rate. It also blocked online platforms that track the black market exchange rate (in a typical ignorant fashion of how the internet functions, as if there is no VPN, Tor, or social media). Needless to say that the permanent state of inaction, uncertainty, anxiety, of economic and social difficulties, was (and still is) a constant during all this period.

The fourth plateau, 15,000-18,000LBP, was reached differently. On June 8, 2021, Banque du Liban issued Circular no. 158, which basically allows small depositors to withdraw per month 400USD in USD and 400USD in LBP at the rate of 3,900LBP (another financial ingenuity by the central bank, still it seemed to progress to the previous situation). Banks went on steroid mode hoarding dollars from the black market. It wasn’t the first time that banks were speculating on the black market. Putting aside the first few months of the crisis, banks seem to be major players on the black market. However, it’s hard to exactly identify and evaluate their role and actions. Ah, and by the way, Circular no. 158 is still not yet properly implemented. The only political event that had a major impact on the exchange rate occurred in the middle of the fourth plateau with the failure of Hariri to form a government after being designated for this task 11 months earlier (the US dollar skyrocketed past 22,000LBP). Nearly one year of waiting, nothing as an outcome, frustration, fear, anxiety, lack of hope… at the end, it seems that effects coupled with speculation are the main drivers for the fluctuations in the exchange rate. But this in no way absolves the political and economic ground which allowed them to foster.

By the way, a new government was formed lately, but this in itself means nothing.

____________

[1] It is very subversive to use terms such as cost of living in a very intuitive and natural way… why does “living” necessitate a cost?

[2] At Müller, they emphatically told me that they lowered the price of a brick from 0.85 to 0.75 USD. To their astonishment, my answer was: no, you increased it by 800% (in Lebanese pounds).

[3] Providing an economic guarantee for all would de facto deal with or solve other issues related to currency depreciation, such as savings in LBP losing their value.